Emil Aaltonen museum

OPening hours

September-May: Wed 12-18, Sat-Sun 12-16.

June-August: Wed 12-18, Thu & Sat-Sun 12-16.

Admission fees

Entry to museum 3€ / 2 €

Museum Card

Payment methods

Credit card and cash

Current exhibition: Footwear – In the Steps of the Past and the Future

25 January 2025 – 25 May 2025

The exhibition ”FOOTWEAR – IN THE STEPS OF THE PAST AND THE FUTURE” showcases the footwear industry and design, as well as education in the field. Through the pages of the Pitsnoukka magazine published by Aaltosen Kenkätehdas Oy, visitors will get a glimpse into the world of the footwear industry in the 1960s and 70s. The footwear produced by the company reflects the development of the industry from the 1910s to the 1980s. The comprehensive presentation produced by the Design programme at Häme University of Applied Sciences highlights the history, present, and future of footwear design education. Also featured are footwear designers who graduated from the institution, Iris Kinni and Hannu Viitala, as well as Terhi Pölkki, who graduated from HAMK and the London College of Fashion, together with Minna Parikka, who graduated from De Montfort University. The ”FOOTWEAR – IN THE STEPS OF THE PAST AND THE FUTURE” exhibition has been realized in collaboration with the Design programme at Häme University of Applied Sciences.

Opening hours and admission fees

Open: Wed 12.00–18.00, Sat-Sun 12.00–16.00. During summer (1.6.–31.8.) also Thursdays 12.00–16.00.

Entry to the museum: 3€ / 2€ / Museum Card. Guided tours are available in Finnish, English, Swedish, German, Italian, French and Spanish. Contact: pyynikinlinna@pyynikinlinna.fi

Permanent exhibitions

Emil Aaltonen Museum of industry and art was opened in Pyynikinlinna on 8.6.2004. The main floor houses works from Emil Aaltonen’s art collection. Upstairs we have other permanent exhibitions: exhibition about Emil Aaltonen (1869-1949), exhibitions about the Aaltonen owned companies, multimedia about the Aaltonen owned Ylikartano mansion and a room where you can watch a movie about the life of Emil Aaltonen. Temporary exhibitions are located upstairs.

Contact information

Emil Aaltonen Museum

tel. 03 212 4551

e-mail: pyynikinlinna@pyynikinlinna.fi

Museum director: Mika Törmä

tel. +358 50 431 4135

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Former exhibitions:

Lauri Eriksson: Metamorphoses (Muodonmuutoksia) 28.9.2024 – 15.12.2024.

Lauri Eriksson (b. 1965) has spent the past few years unravelling and transforming autobiographical events and layers of his daily experience into textual and photographic compositions. His self-portraits, landscapes and fleeting impressions evince a sense of collective yearning expressed through shifting interactions between self and context. His photographs and texts are interwoven in rhizomal tapestries of words, things, places, materialities and social dimensions that capture the complex interactions of modern existence. All things exist in a constant state of transition: individuals, social relations, cities and natural formations are all incessantly evolving, each at its own pace, following its own unique path and stages of metamorphosis. Change is ultimately about becoming.

Ulla Jokisalo, Jorma Puranen, Pentti Sammallahti: The Beauty of Moments 16.6.2024-15.9.2024

How long does a moment last? The moments of taking a photograph and taking a loot at it are so different in duration that when you compare them, it is like timing with a clock that has no hands. Photographs simultaneously contain a variety of times: the objectively measured passage of time in seconds and minutes, planetary time, which has something to do with the world of animals (and perhaps children), or the flowing passage of time in personal experiences, among others. Photographs are moments from the past, yet viewed in the present. Viewing photographs is thus a temporal back-and-forth movement between the past and the present. The oldest photograph in the The Beauty of Moments exhibition is from 1970, and the latest ones are from a few years ago.

Beauty is a concept that has long been considered problematic in contemporary art. After more than half a century of suspicion, the discussion on the subject of beauty has once again gained a foothold in the visual arts. However, beauty no longer has a single, universal meaning; instead, it has many interpretations, and it is always personal. Along with the democratization of photography’s themes and values, no theme is more valuable or beautiful than another in photography. Therefore, the beauty of a photograph must be discovered elsewhere, somewhere in the relationships between its contents and the observations thereof. The beauty of a photograph might be about enabling us to take a closer look at those moments, which are mercilessly bypassesed by the normal passage of time. Beauty is also about exposure to the world and submission to it, the expanded relationship between the self and the world.

The works of the three photographers in the The Beauty of Moments exhibition are recordings of these encounters with the world. They express intimacy and provide understanding of the porousness of the human boundaries.

Ulla Jokisalo (b. 1955) began her photography studies at the University of Art and Design in 1977 and had her first solo exhibition in 1983, and she has worked as a freelance photographer and artist ever since. Jokisalo regards herself as a storyteller who, like a flâneur, wanders through the flow of images, letting her imagination to be reflected on it.

Jorma Puranen (b. 1951) graduated from the University of Art and Design in 1978. It was already during his studies that he began his long-term work in the northernmost regions of Lapland. He early adopted a museum and archive-based approach to his work. The relationships between history, knowledge, landscape, and culture are central parts of his art.

Pentti Sammallahti (b. 1950) began photographing at the beginning of the 1960s. He is one of the first Finnish photographers to have achieved a lifelong career as a photographic artist. His photographs are labelled by their warm humour and the enchantment of black-and-white photography. Sammallahti belongs to the most internationally recognized Finnish photographers.

Pyynikinlinna 100 years 24.2.2024 – 2.6.2024

Valoa ja kuvia Pyynikinlinnan kokoelmasta 21.10.2023-11.2.2024

Muovi – Eilen, tänään, huomenna 22.4.2023 – 8.10.2023

Susanna Majuri: Sense of Water 20.1.2023-2.4.2023

Jouko Lehtola: Rock-Finlandia 17.9.2022-18.12.2022

Feelin’ Relaxed – Naivist Art from the Collections of the Oulu Museum of Art 19.3.2022–28.8.2022. (Exception: 18.5.2022 Wed 12.00-16.00.)

Nanso 100 – 4.9.2021–27.2.2022

150 years of Emil Aaltonen 29.8.2019–1.12.2019

On 29 August 2019, we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the industrialist Emil Aaltonen. The jubilee exhibition has its focus on the different aspects of Emil Aaltonen’s character.

“The dark blood of Aaltonen does not glow on the surface, heating up beneath the calm surface like fire in the tar pit. But the warmth and its influence are still as effective.” This was the way Suomen Kuvalehti, a Finnish magazine, described Emil Aaltonen when this man of honorary titles turned 70 years in 1939.

This factory owner was known as a demanding employer in Tampere, but also as a person with a deep belief in fairness. In both work and private life, Emil Aaltonen’s guiding principle was service; another person’s well-being was also about his well-being. Aaltonen also wanted to challenge himself constantly: “Life is battle, it is battle with oneself and one’s tendencies. Winning yourself is the greatest victory.”

The Other Self – Paintings by Raimo Utriainen 26.5.2019–11.8.2019

Raimo Utriainen (1927–1994), the sculptor, is best known for his constructivist sculptures made of thin metal slats placed together in a mathematical style. The peaceful forms of his abstract works as well as their surfaces that vibrate in the light remind us of natural phenomena. They are not a copy of the visible, however, since they are based on forms and rhythms that exist underneath the surface as building blocks of the visible world. There was also something else about Raimo Utriainen. While working on his most subtle sculptures, he also made large-scale paintings with powerful colours and gestures, often suggestively figurative. This was his way of expressing suppressed emotions that had no space in the ascetic minimalism of his sculptures. The majority of the paintings were made in the 1980s, during the golden era of new expressive painting. Raimo Utriainen was acknowledged as one of the great reformers of modern Finnish sculpture. His canvases, which are both strong and delightful at the same time, sometimes even grotesque, prove that he was on the pulse of the times even when he was painting.

At The Source Of Technical Creativity –Drawings From Lokomo And Sarvis 16.2.–19.5.2019

The exhibition is focused on product development conducted from the 1920s until the 1980s by the steel workshop Lokomo and the plastic factory Sarvis. Innovative and unconventional designing is essential for successful business. It was the emphasis on design that turned both Lokomo and Sarvis into frontrunners in their fields in Finland and abroad. Their product development is presented through drawings, objects, and photos. In addition, we will display scale models of machines manufactured by Lokomo.

THE EARLY YEARS OF SHOE MAKING

All over the world, until the mid-1800s, shoes were made by hand. Technological innovations then made it possible to produce shoes industrially in mechanised plants. The first shoe factories in the leading industrial nations were founded towards the end of the 1850s.

Finland’s first shoe factory, Tampereen Jalintehdas, began operations in 1875 near Hämeenpuisto Park. Its first efforts remained, however, short-lived. Only the factory in Korkeakoski, founded at the end of the century, managed to establish operations that lasted into modern times. It was also at the turn of the 20th century that Emil Aaltonen’s workshop in Hattula was turning into a mechanised shoe-factory.

One problem shared by all Finnish pioneers in shoe manufacture was the nation’s prejudice against factory-produced footwear, an attitude further promoted by shoe makers who feared losing their jobs. At the turn of the century almost all Finns were wearing hand-made shoes and boots. Society was changing, however, from a subsistence economy to one based on commodities and money. This transformation was most clearly visible in an industrial town like Tampere where labourers had to buy all their necessities, e.g. clothes and footwear, with money.

APPRENTICESHIP YEARS

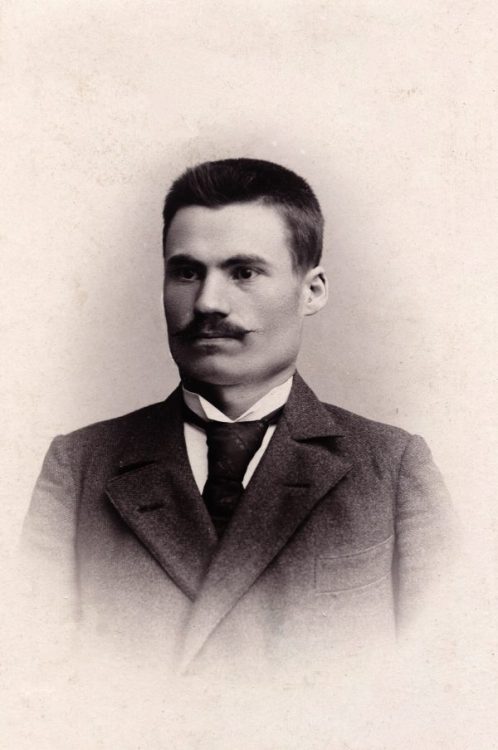

Emil Aaltonen (Widell until 1890) was born in into a smallholding family in 1869 in the village of Metsäkansa in Sääksmäki. Following the famine years, the family lost the farm and Emil’s father went to work on the railway in Toijala. His father died when Emil was only ten years old, and the family’s seven children were brought up by his mother.

Emil, who had dreamt of becoming a blacksmith, was, apparently because of his physical frailty, sent to become a shoe-maker’s apprentice at the age of 13. Shoe makers would travel, with their apprentices, from house to house, carrying only the necessary tools of their trade: lasts, a knife, an awl, pincers and a hammer, wooden nails and pitched cobbler’s thread. An apprentice’s annual wages were a pair of trousers, a shirt and a pair of shoes.

After three years as an apprentice Emil worked for two more years for Master Grönlund in Nihattula where he learned to make and repair finer shoes and boots.

BECOMING AN INDEPENDENT ENTREPRENEUR

Emil Aaltonen was 19 years old and a master shoe maker, when he began as an entrepreneur, first on his own – soon with his younger brother as apprentice – in a rented space in Nihattula. At first winters were spent, as before, touring the countryside from house to house. At the workshop too footwear was made by hand with just one sewing machine to help. Aaltonen gleaned experience from the more demanding commissions he received from Russian officers posted in nearby Parola. And, in contrast to some masters who even refused to repair factory-made shoes and boots, Aaltonen purchased factory-made footwear from his clients, and then took it apart carefully in order to see how it had been made.

Emil Aaltonen (1869-1949)

Aaltonen then acquired larger premises on Hattula’s Linnamäki-Hill. The number of sewing machines rose to ten and at its largest the workshop employed 15 workers. His goods sold well, both in Helsinki and in Hämeenlinna where Aaltonen had two shops.

In 1896 he married Olga Malinen. It was on his wife’s initiative that the goods’ selection widened to include oilskin coats and tobacco pouches and gloves made out of leather off-cuts.

Hattula Footwear Factory

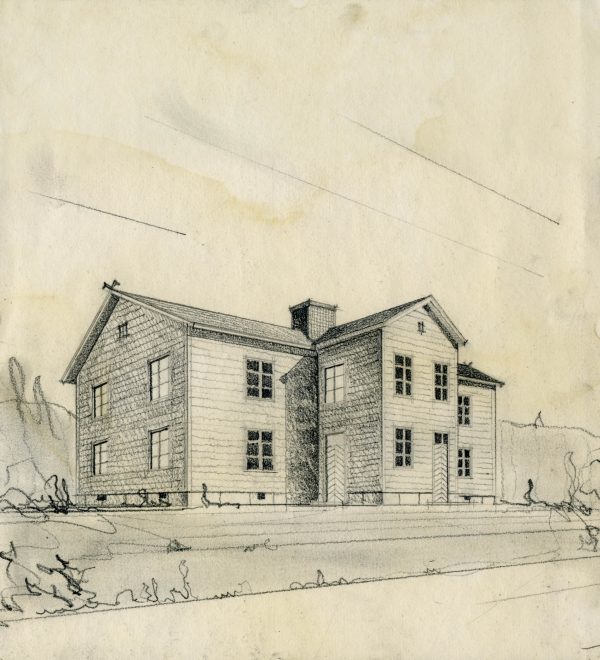

In 1902 Emil Aaltonen bought some used, originally American, machines and founded Hattula Footwear Factory. Production expanded, and the old premises became too small. A two-storey log-built factory, designed by Aaltonen, was completed in early 1904. There were 50 workers, and the same number of shoes were made each day. The factory-made shoes sold well, since they were found to be good value and long-lasting.

In the winter of 1905 the factory burned down completely and only some of the machines could be saved. But worse was to come. In May, his wife Olga Aaltonen passed away. The troubled industrialist considered various options: giving up shoe making or building a new factory in Hattula, Hämeenlinna or Tampere.

TAMPERE SHOE FACTORY

Emil Aaltonen chose Tampere as the location of his new factory. Tampere was already an industrial town. Of almost 40 000 inhabitants, two thirds worked in industry, mainly in textiles. There was no shoe factory in Tampere.

Aaltonen bought the buildings of the bankrupt Tampere Cane Factory in Tammela at Kyllikinkatu 19, where production was started already in 1905 under the name Tampere Shoe Factory. Operations got swiftly underway so that in its first full year the number of workers grew to 100 and production to 20 000 pairs.

Employees in front of the Tampere Shoe Factory in 1907.

Soon after Tampere Shoe Factory other shoe factories were established in Tampere. Some of them grew to be large competitors to Aaltonen’s production plant. In 1910 as much as 75% of the entire country’s footwear production was in Tampere which thus came to be known as the capital of shoe-makers.

To expand his operations, in 1910 Aaltonen purchased the neighbouring block on Tammelan Tori, newly vacated by a wallpaper factory, and transferred operations there. Between 1913 and 1928 a beautiful factory building, designed by the architect Lambert Petterson, took over the entire block.

AALTONEN SHOE FACTORY

Tampere Shoe Factory was made a shareholding company (Osakeyhtiö or Oy) in 1917 under the name Aaltonen Shoe Factory (Aaltosen Kenkätehdas Oy). Control of the company remained in Aaltonen’s hands. It had become large, its employees making up a third of all workers in the country’s footwear industry.

Aaltonen Shoe Factory’s key social contribution was to make it easier for its workers to find housing. For example the company constructed large residential blocks, Pikilinna (1924), Sorsapuisto (1937) and Akonlinna (1941). By offering low-interest loans to employees it also helped them construct their own houses.

AALTONEN SHOE FACTORY’S ASSOCIATE COMPANIES

The war years were generally a period of growth for Tampere’s shoe factories. Their greatest challenge was the depression of the 1930s during which even large plants were closed down. Of these, Aaltonen bought two of the better known ones, Attila and Solena. Korkeakoski Shoe Factory had been bought already. The division of labour between these plants was such that Solena manufactured lighter shoes for ladies, Attila welted shoes for men and women, and Korkeakoski boots and shoes for men.

Korkeakoski Shoe Factory

The plants operated as sister companies in competition with each other until 1940 when they were merged into Aaltonen Shoe Factories. The Company had over 1300 employees.

To secure raw materials for the growing production, Aaltonen gained ownership of Viiala leather factory in 1925. After its expansion it was capable in practice of satisfying the leather needs of all the company’s plants.

In 1936 Aaltonen Factories purchased Teknika, a factory making different chemical products, including shoe dyes.

CONSUMER PREFERENCES

The Hattula Footwear Factory mainly made black ankle boots. In the 1910s the Tampere Shoe Factory produced about twenty models a season. Fashions were of only secondary importance after durability, comfort and value for money.

At the end of the post-First World War slump, Europeans became conscious of changing fashions. In rural Finland habits died slowly and the black ankle boot remained popular. In the towns, however, people followed European fashions and admired foreign footwear. Aaltonen Shoe Factory, for whom the emblematically Finnish trademark Vakuuskenkä (Assured Shoe) had been so important, set to developing ladies’ fashion shoes under, among others, the Nelly-trademark.

After the depression, towards the end of the 1930s, Aaltonen Shoe Factory’s range grew to include about 4 500 models, and from two colours, black and brown, its colour choices expanded to almost 600.

OY LOKOMO AB

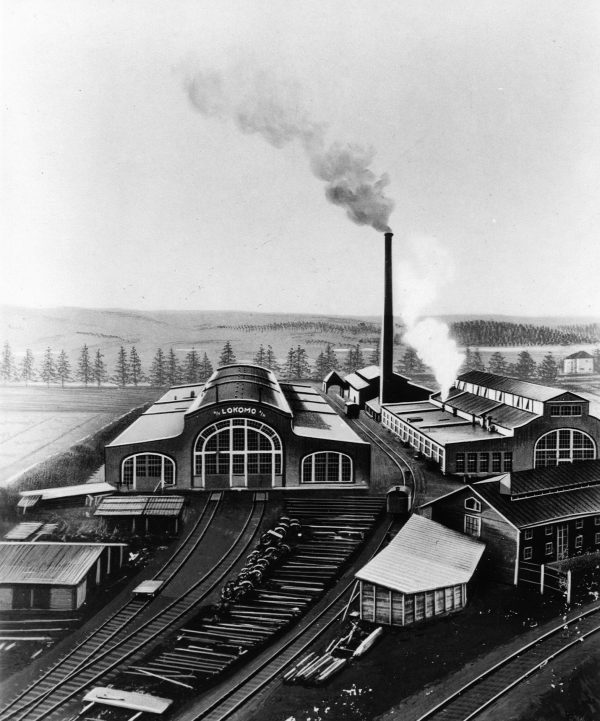

Oy Lokomo Ab was established in Tampere in 1915 as a locomotive factory. Emil Aaltonen was one of the original share holders. After ten years it transferred practically in its entirety into Aaltonen’s ownership.

Lokomo factories in Hatanpää, Tampere.

In addition to locomotives the factory produced anvils, road-building equipment, anchors and tramway components among others. The cellulose industry and Ministry of Defence were significant customers in the 1930s. During the Second World War, Lokomo worked primarily for the national defence forces after which war reparations kept it busy. Under Aaltonen’s ownership the company grew into a production plant with 1 300 employees.

SARVIS OY

Founded in 1921, Sarvis was the country’s first plastics manufacturer. Aaltonen was enticed by shares in the company – and later to take it over almost completely – because it offered the opportunity to utilise, in manufacturing itself, residues left over from the production of skimmed milk at his estate in Mäntsälä.

Sarvis produced galalith, which resembled genuine bone and horn. At first it was used to make buttons, combs, pens and sewing tools. After a couple of years began the production of lamp shades which were to become extremely popular.

First Sarvis factory in Hatanpää, Tampere.

When, after the Second World War, the plastics industry really took off, Sarvis with its 400 workers was among the largest in the country. The factory produced components for the automobile, aircraft, and textiles industries among others, and even such unexpected products as cameras and vinyl records.

LEISURE

The visual arts and farming were most prominent among Emil Aaltonen’s pastimes. He was also interested in, for example, astronomy.

Aaltonen created a collection of 250 art works, sizeable in the Finnish context, part of which is now on show in Pyynikinlinna. His first art purchases were made in the 1920s already, but it is only possible to speak of a real collection two decades or so later. A main motive for acquiring Pyynikinlinna was probably to house the collection properly.

Having spent his childhood in the countryside, Aaltonen was always drawn to farming. In 1917 he purchased Andersberg, or Ylikartano, in Mäntsälä, an old aristocratic but run down estate. It comprised 2 600 hectares, 850 of which was under cultivation. Livestock included hundreds of cattle and about a hundred horses, among others.

Aaltonen improved the estate so that it became a link in an industrial production chain.

His innovations were particularly forward thinking. For example, the casein from the estate’s own dairy was taken to Sarvis where it was made into galalith. Being proprietor of a locomotive factory, he had four-kilometres of narrow gauge railway constructed to facilitate harvesting around the estate.

DONATOR

Emil Aaltonen felt that growing economic well-being was only possible where national culture was on a high level. And so he wanted to give a portion of the wealth he had created in support of Finnish culture.

Aaltonen gave the city of Tampere the necessary capital for building a new library. When it was finished, a memorial statue for the author Aleksis Kivi, by Wäinö Aaltonen, was erected at its entrance, also largely financed by a gift from Aaltonen.

He created the Emil Aaltonen Foundation to support Finnish-speaking scientific research.

The University of Turku received several gifts. Of particular significance was Professor U. L. Lehtonen’s collection of almost 4 500 volumes, purchased for the University Library.

To his parish of birth, Metsäkansa in Sääksmäki, Aaltonen donated a village church. He also helped finance the construction of churches in Korkeakoski and Viiala.

Emil Aaltonen Foundation’s first meeting in Pyyninkinlinna, in Aaltonen’s study in 1937. From the left, Lauri J. Kivekäs, Professor Olli Heikinheimo, Emil Aaltonen, University Chancellor Hugo Suolahti and Professor V. A. Koskenniemi.

Pyynikinlinna is located in the peaceful, garden-like quarter of Pyynikki, built in the early years of the last century. Pyynikinlinna’s windows, balconies and garden look out over the pine trees of Pyynikki’s park to lake-Pyhäjärvi as well as towards the city centre, only a kilometre away.

Designed by the architect Jarl Eklund, Pyynikinlinna was completed in 1924. It is a two-storey building, painted white over a plastered brick construction and features many classical details. It demonstrates an admiration for ancient Greek and for Italian architecture, and shows its adaptation into twentieth-century Nordic classicism.

Pyynikinlinna was the long-time home of Emil Aaltonen (1869-1949), pioneer of Finnish shoe manufacture. His descendants lived there after his death. Aaltonen purchased it in 1932 to be his home but also to house his expanding art collection.

In 1984 Aaltonen’s grand-daughter, Eila Kivekäs, had Pyynikinlinna refurbished so that it could accommodate exhibitions and public events. Architect Markku Komonen designed the alterations so that the building’s original façade as well as its atmosphere of private domesticity would be preserved.

From 1983 to 2000 the building was administered by Kannus Production Oy which organised numerous exhibitions of contemporary art as well as, among other things, four exhibitions focussing on West African culture. It was during that period that the Pyynikinlinna art collection, still being augmented with private funds, was born.

In June 2004 Pyynikinlinna became the home of the Emil Aaltonen museum of industry and art. The permanent collection, located on the main floor, represents Aaltonen’s life and displays some of his art collection. The exhibited artists are masters of older Finnish painting, Alexander Lauréus, Werner Holmberg, Albert Edelfelt, Fanny Churberg, von Wright-veljekset, Pekka Halonen…

The top floor houses temporary exhibitions.